I recently completed a comprehensive specification for Pharmacokinetics Grapher, a Vue 3 + TypeScript web application that visualizes medication levels over time. What started as preplanning notes evolved into a 461-line specification document through rigorous dual-agent review (Gemini + Codex), uncovering critical mathematical and domain issues that would have shipped bugs.

This post documents the journey of building a pharmacokinetics specification—the process, the problems we discovered, and why specification review matters for scientific software.

The Challenge: Why Pharmacokinetics is Hard

Building a pharmacokinetics visualization app isn’t just UI engineering—it’s applying pharmacology, mathematics, and domain knowledge under pressure. Users will enter prescription data expecting accurate peak/trough predictions. Get the math wrong and you don’t just have a buggy app; you have a dangerously misleading medical visualization.

The requirements were deceptively simple:

- Users input: drug name, dose, frequency, half-life, absorption time

- App outputs: concentration curves showing peak/trough patterns over time

- Multiple drugs can be compared on the same graph

- Prescriptions save to browser storage

But “simple” requirements hide complex decisions: Which pharmacokinetics model? How do we handle multi-dose accumulation? What if absorption time equals half-life (ka ≈ ke)—a mathematical singularity? Should outputs show absolute mg/L or relative concentrations?

The Journey: Discovery Through Review

I started by drafting a specification from preplanning notes. It covered the basics: Vue 3 architecture, TypeScript types, the one-compartment pharmacokinetics model, testing strategy. It looked complete. Then I ran it through a dual-agent review with Gemini and Codex.

The review found 4 critical issues:

Issue 1: Absolute vs. Relative Concentrations (Vd/F Problem)

The specification initially proposed outputting absolute mg/L concentrations. This is standard in pharmacology—show the user exactly how much drug is in their bloodstream.

Problem: To compute absolute concentrations, you need Vd (volume of distribution) and F (bioavailability). Neither is provided in a pharmacy insert. The user has no way to input these values, yet the math requires them.

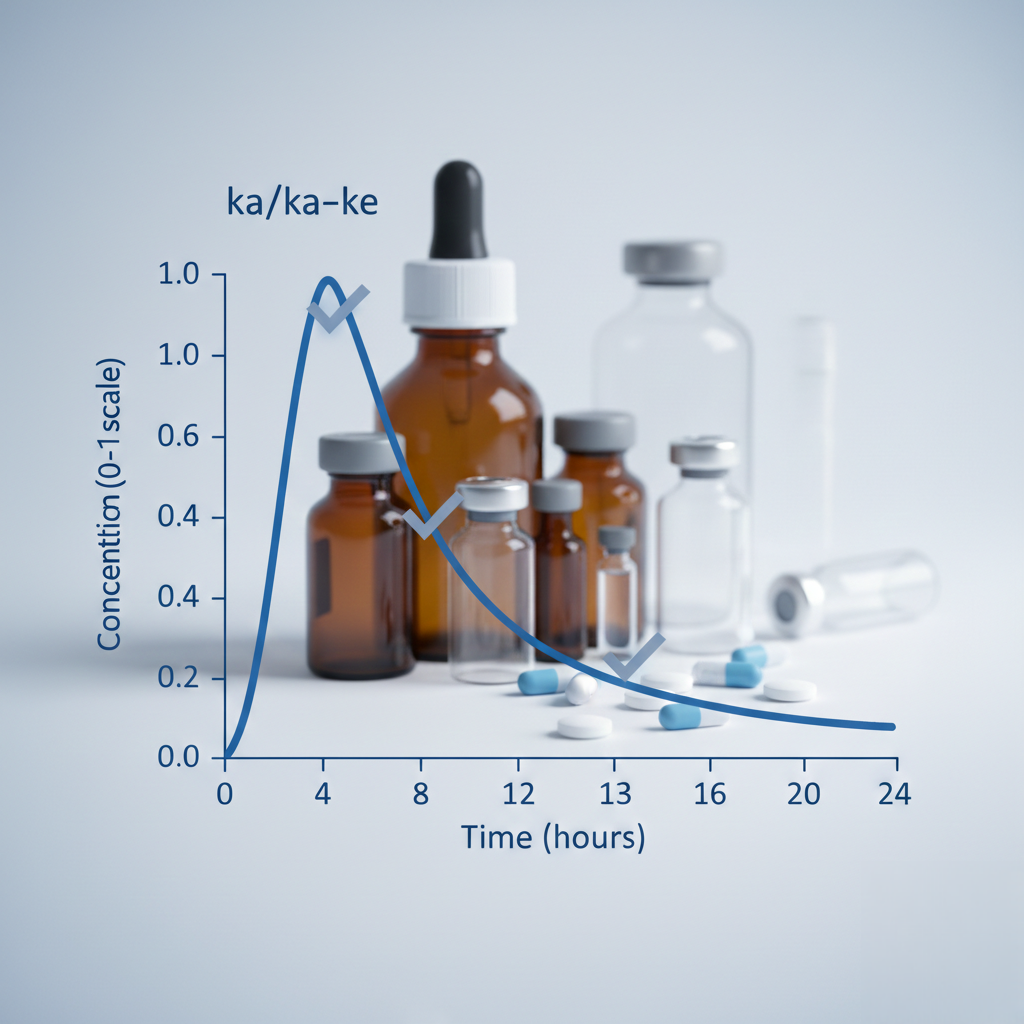

The review surfaced this gap. The solution: output normalized relative concentrations (0–1 scale) instead. This shows the shape and timing of peak/trough patterns without requiring unknowable patient-specific parameters. It’s honest about what we can visualize and prevents misuse for actual dosing decisions.

Issue 2: ka ≈ ke Edge Case (Mathematical Singularity)

The standard one-compartment equation is:

C(t) = Dose × [ka/(ka - ke)] × (e^(-ke×t) - e^(-ka×t))When absorption time (1/ka) equals half-life (related to ke), the denominator ka - ke approaches zero—mathematical instability. The review caught this and asked: what happens when a user enters these parameters?

The specification originally had validation to reject this case. But real drugs can have ka ≈ ke (slow absorption, fast elimination). Rejecting them is medically wrong.

The fix: soft validation with fallback formula. When |ka – ke| < 0.001, switch to the series expansion form that handles the singularity:

C(t) ≈ Dose × ka × t × e^(-ke×t) [when ka ≈ ke]Warn the user it’s unusual, but don’t block it. Handle the math correctly.

Issue 3: Pharmacy Insert Sourcing (Ranges, Not Values)

I assumed pharmacy inserts gave exact values: “half-life 6 hours.” Actually, they give ranges: “half-life 4–6 hours.” The user picks a representative value within that range.

This insight reframes the app: we’re visualizing approximate behavior within typical ranges, not predicting exact drug levels. This justifies the normalized relative output and softens the validation philosophy. Users aren’t trying to match exact numbers; they’re understanding typical patterns.

Issue 4: Multi-Dose Accumulation (Sum-Then-Normalize Order)

For multiple doses, the math must be exact. Initial approach: normalize each dose’s contribution, then sum. Wrong. The correct order: sum all raw dose contributions, then normalize the total curve to peak = 1.0.

Why? Because accumulation is additive—each dose adds to what’s already in the system. Normalizing per-dose then summing breaks the mathematics and gives false peak ratios at steady-state.

The review caught this mathematical error before it shipped. The specification now documents the correct approach explicitly.

Technical Details: The Specification

After resolving these issues, the specification crystallized around key decisions:

Architecture: Pure Calculations, Dumb Components

Core calculation functions are pure (no side effects):

calculateConcentration(time, dose, halfLife, uptake): number

accumulateDoses(prescription, startDateTime, endDateTime): TimeSeriesPoint[]

getGraphData(prescriptions, timeRange): GraphDataset[]Vue components are thin UI layers that call these functions. This separation makes testing straightforward and allows the same math to power different visualizations later.

Model: One-Compartment, First-Order Absorption

Simplified but sufficient for MVP. Assumptions:

- No drug-drug interactions

- Linear kinetics (no saturation)

- Complete absorption (F = 1.0)

- Negligible active metabolites

These are documented as assumptions, not hidden gotchas. If future use cases need two-compartment kinetics (metabolites), we can extend without rewriting everything.

Validation: Permissive With Warnings

The specification philosophy: allow users to enter atypical parameters with warnings. Why? Because their source data (pharmacy insert) might have atypical characteristics. The goal is visualization, not rejection.

Only special-case: uptake ≈ halfLife triggers the ka≈ke fallback formula (not a hard error).

What We Learned

1. Domain specification review pays immediate dividends. We caught 4 issues before writing a single line of implementation code. Each would have required rework later or shipped as a bug. The dual-agent review cost maybe 2 hours; the bugs would have cost days.

2. Scientific software needs mathematical rigor, not just code correctness. Passing tests means nothing if the equations are wrong. The specification now has specific mathematical references (one-compartment model, first-order absorption) that can be verified against pharmacology textbooks.

3. Edge cases are features, not bugs. ka ≈ ke is rare but real. Instead of rejecting it, we handle it with a fallback formula. This makes the app more robust and honest about what it can do.

4. Normalize relative outputs, not absolute. Without patient-specific Vd/F values, absolute concentrations are noise. Relative curves show shape and timing—what users actually need to understand dosing patterns.

5. Specifications are code too. CLAUDE.md is 461 lines of decision documentation. It’s not casual English prose; it’s precise technical writing with equations, validation rules, and explicit assumptions. This level of rigor makes implementation straightforward—there’s no ambiguity about what “correct” means.

What’s Next

With the specification locked in (and verified through rigorous review), implementation can begin with high confidence:

- Scaffold Vue 3 + TypeScript project with Vite

- Implement core PK calculations (pkCalculator.ts) with unit tests using reference fixtures

- Build prescription validation and storage layer

- Wire Vue components (PrescriptionForm, GraphViewer, PrescriptionList)

- E2E testing with Chart.js visualization

All guided by the CLAUDE.md specification—no ambiguity, no rework. That’s the payoff of rigorous specification through review.